‘An ‘ART’ Revolution: Procreation and Kinship in a Gestational Care Facility’ by Oshin Siao Bhatt

MA Fine Art and Design, The Critical Inquiry Lab (2020-2022)

Design Academy Eindhoven, Eindhoven, The Netherlands

Key supervisors: Danae Io and Callum Copley

The project, 'An ‘ART’ Revolution: Procreation and Kinship in a Gestational Care Facility in the Netherlands' was conceived and produced as part of a class on ‘Possible Histories and Contingent Futures’ in the Critical Inquiry Lab Master at the Design Academy Eindhoven. The final outcome took the shape of a speculative ethnography of a fictional clinical facility centred around assisted reproduction, in an alternative present. The text was shaped as an academic paper written from the perspective of two medical anthropologists, and paired with supporting images of the imagined space, artefacts, and experiences. Through these media and the use of retro-speculative world building, the project sought to delve into the ‘promissory’ role played by reproductive technologies and substances, and the influence of specific clinical settings, language and practitioners in furthering this rhetoric. In this way it also sought to question normative notions of ‘desired (familial) futures’ and unpack the implications of assisted reproductive technologies on questions of gender, race, class, religion, etc.

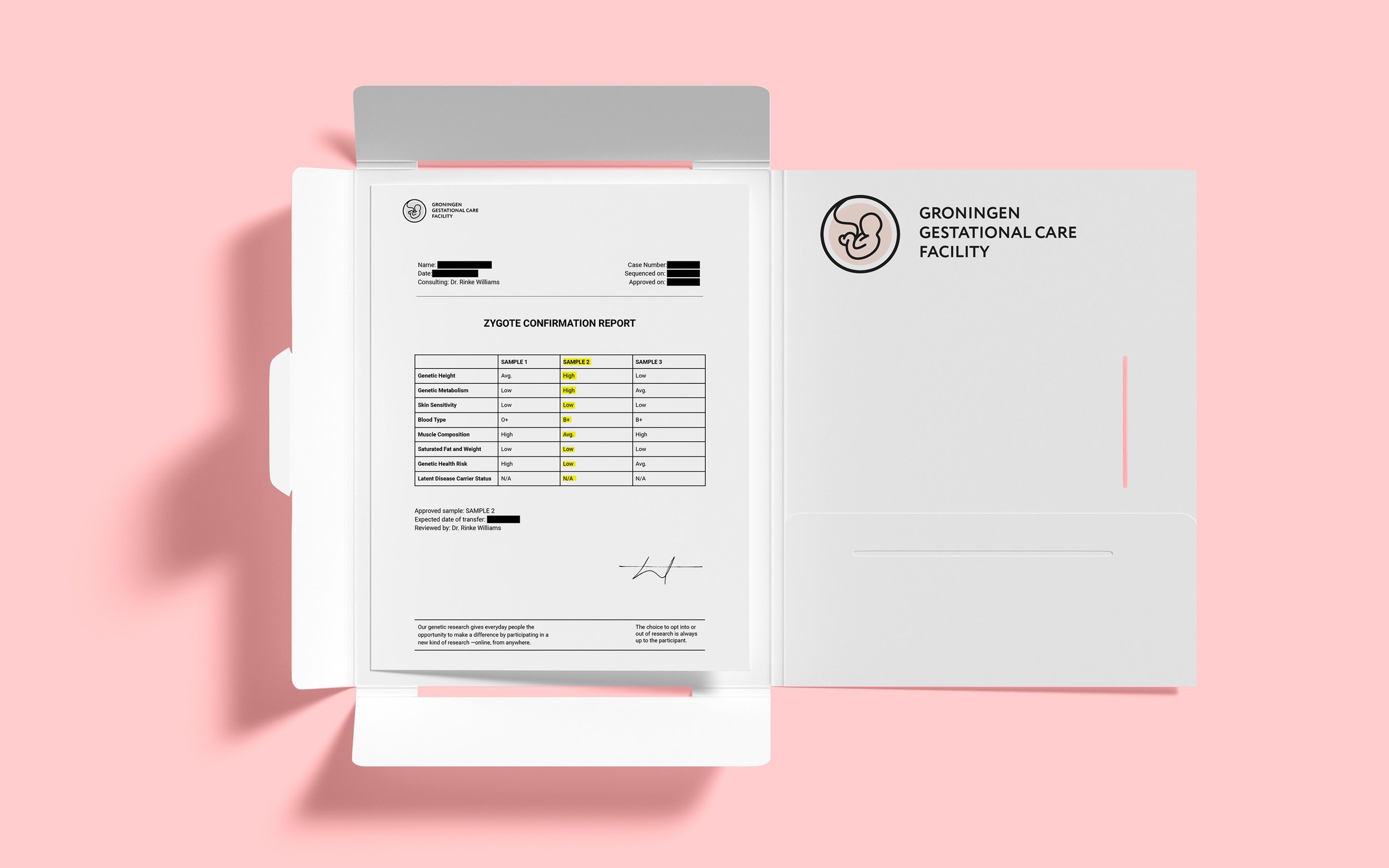

Drawing from actual ethnographic work around reproductive technologies and clinical spaces at large, the narrative imagined a world where technologies that assist in processes of conception and birthing have become increasingly inventive and readily available. In this world, the Gestational Care Facility became the central clinical space for the navigation of reproductive services ranging from ‘Assisted Parthenogenesis’ to ‘Extracorporeal Gestation’, and even routine counselling around these processes. Through the use of existing as well as fictional studies and theoretical concepts, the project explored the notion of a child-to-be as symbolic of the idea of birthing futures; while the spatial exploration provided the possibility of thinking through how this symbolism played out. The creation of artefacts, moreover, added different layers to this spatial narrative, including a certain legitimacy introduced by the branding; a sense of normalisation around these processes represented by the waiting room poster and the folder containing test results; as well as a call for the suspension of disbelief brought in by the Extracorporeal Womb itself.

The text itself was primarily centred around the stories and experiences of different intended parents, each embodying not only a different technological feat available at the Gestational Care Facility, but also diverse socio-cultural and economic realities. The images complemented these stories by outlining the experiences within the clinical space. While the nuances and details of these narratives were entirely speculative, they drew heavily from real case studies encountered during primary or secondary research around existing reproductive technologies and clinical spaces. These stories tackled questions around kinship, blood ties, the imagination of relatedness, stratified reproduction, desirable futures, access to medical interventions, medical tourism, etc. One of the cases, for instance, involved a single woman attempting to undergo an ‘assisted parthenogenesis’ procedure in order to have a child of ‘own’, bringing forth the notion of ‘blood ties’; which has been questioned by Janet Carsten (2001) on the grounds that blood is one of the only substances that does not perfuse through the placental membrane, and in that sense is never shared. Within this world, however, this analysis took on an altogether different meaning given the use of ‘Extracorporeal Wombs’ that ensure the separation of all bodily fluids between a parent and child.

Other narratives like that of the Kumars highlighted the normative nature of a particular kind of desirable future, forged through the imagination of relatedness and parental responsibilities towards a future child. Drawing on the pro-natalist stance of certain cultures, this story presented a couple undergoing the process of selecting the ‘perfect’ zygote in order to ensure an ‘ideal’ future for their unborn child. What was key within this case, however, was the conflation of married couples’ identities at large, and women’s identities in particular, with parenthood and the responsibilities that come with it. The experience map connoting this situation allowed the possibility of highlighting touch points that deviated from a technology driven spatial encounter, such as the importance of counselling and care work within the Gestational Care Facility. The cases of Maria and Lucy, Rik and Thomas, and the Mahmoudis on the other hand became indicators for the phenomenon of ‘stratified reproduction’ as defined by Rayna Rapp and Faye Ginsburg (1995) - ‘the hierarchical organisation of reproductive health and technology and the ways in which it rewards the maternity of some women, while pathologizing that of others.’ Within the scope of this project, this stratification was expanded beyond just motherhood to include gay couples struggling to have biological children owing to technological limitations, high financial stakes excluding those with monetary constraints, as well as barriers based on religious grounds. The setting of the scene, through descriptions of the waiting rooms and visual representations then, became key in highlighting the inequality of access pervasive in the world of medicine and biotechnology, and reflected in this speculative exploration.

Oshin Siao Bhatt / MA Fine Art and Design / Design Academy Eindhoven, 2020-2022

Oshin Siao Bhatt is a Master student at the Critical Inquiry Lab at Design Academy Eindhoven. She has a background in Sociology, Social Anthropology and Design Research and is interested in exploring the mutual relationship between the shifting landscape of biotechnology and changing socio-cultural realities, norms and belief systems.

science fiction, healthcare, clinical spaces, biotechnology, assisted reproductive technology, reproduction, artificial womb, parthenogenesis, procreation, nurturance, kinship, parenthood, aspirational futures, blood ties