‘Destabilised Common Grounds’ by Nirit Binyamini Ben-Meir

MA Information Experience Design (2019-2021)

Royal College of Art, London, UK

Key supervisors: Charlotte Jarvis, Dr Dylan Yamada Rice, Dr Claudia Dutson.

How can we promote reciprocity after centuries of extraction of human and natural resources? The coronavirus crisis exposed our societies’ vulnerabilities and the disastrous ecological implications of nurturing competition and hierarchy.

Destabilised Common Grounds is a set of performative installations and workshops revealing the wisdom of moss colonies. It invites a deep engagement with a fascinating community that we tend to overlook - mosses. Mosses grow in colonies of independent strands. The density of the colony supports the individuals and protects them. In addition, the colony stabilises the soil and set conditions for other plants to grow and prosper.

The work is based around moss colonies that have been growing on a domestic doormat. Coming from the dry country of Israel, the presence of moss in the cityscape of London made me curious. Through my daily journey, I noticed these plants appear and disappear regardless of the seasons. One day they were there. The next, they were gone. So I started to explore them. During one of my walks, I spotted a damp doormat with some moss growing on it. I asked the owner if I can adopt it. I have been taking care of it since then.

It was fascinating to discover the dynamic mechanisms of the moss colonies and their incredible tolerance to stressed conditions. I found that moss colonies could act as a counter-model to neo-capitalism.

Mosses are ancient bryophytes; they are simple yet resilient. They are uncompetitive, they grow very slow and very low, and they usually grow where other plants can not. Scholars claim that moss is a significant contributor to the ecology of the earth.

The ability to exist in the most stressed conditions derives from the mosses rapid reaction to the environment, its regulated use of resources, and its unique life cycle in relation to time. Thus, the moss's life cycle is not tuned according to hours, days or seasons, but it is synchronized to the number of available resources.

What if corporations and businesses would be more modest and temperate? What if they would utilize the exact amount of resources they need to maintain activity without the aim to constantly and endlessly grow. Overactivity, overgrowth, overconsumption are all sicknesses of our current civilization. This capitalistic, excess routine makes the whole ecosystem more vulnerable and unprepared for stressful times; certainly, it is not harmonized with environmental changes. The current world crisis of the Coronavirus pandemic created extreme and unique conditions, which might allow the human society to re-examine its values and its definition of ‘smartness’.

In this project, I investigate how the interaction with a biological entity activates kinship and introduces a shift in the meaning of value. In addition, I am interested in researching how the relationship between humans and other-than-human (plants, insects) can reflect on power relations between different groups of society.

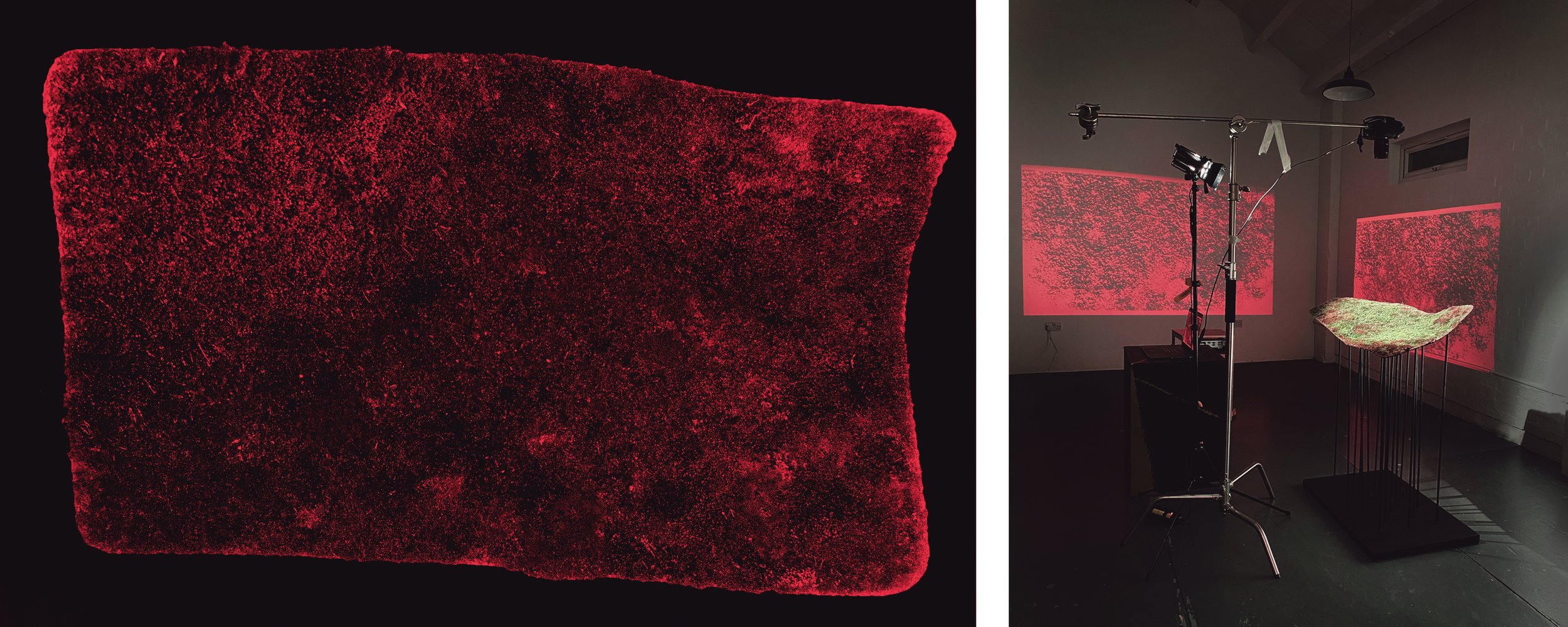

Audiences are invited to influence the moss’s climate and see the impact of their actions on the moss landscape’s condition in real-time. Two large projections show the moss’s reaction in real-time: One through a macro-lens view showing the movement of the strands, which are very responsive to water or to dry air. Another shows the moss through a red filter that emphasises the dry and vulnerable areas and acts as a climate map. In addition, the visitors can see what is happening when others dry or wet the moss in real-time. The participants’ interventions act as a metaphor and reflective tool to human and non-human relationships and the impact humans impose on the environment.

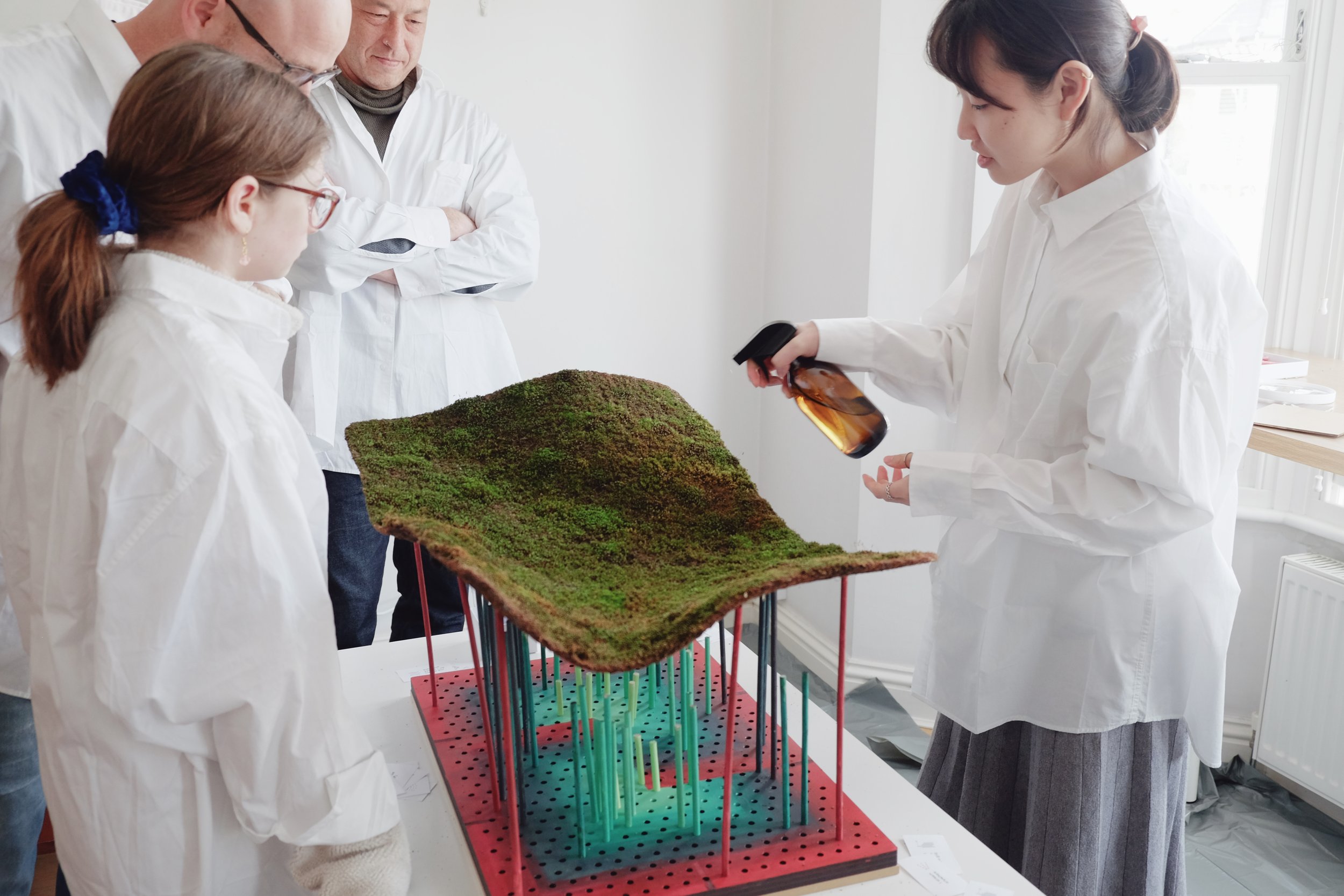

In addition to the participatory installation, I designed a workshop for expert groups such as sociologists, economists, architects, and policymakers looking for new methods to tackle inequalities and geopolitics. In this workshop, the moss rug acts as a board game. Each player gets a territory. Their goal is to keep it the greenest and most prosperous area on the rug. Then, through playing cards, they get to use water spray, hot air to dry others’ areas, and an option to manipulate the rug’s topography.

The group started the game under the familiar motivation of competition. However, gradually they developed empathy and care towards the moss. The players also realised all of their actions affect the whole rug and their own territory as well.

They started to collaborate to try and balance the rug and make sure everyone strives.

The video 'Shared Breath' is showing me breathing on moss. The humidity from my breath feeds the moss and activates it to breathe through photosynthesis. It releases oxygen back to me. This is a slow, poetic and meditative experience.

It offers an optimistic perspective and shows humans are needed in this biosphere; Kinship can be as simple and intuitive as breathing.

This project sees the vital link between society and ecology and proposes bio-entities to aid true reciprocity within communities and the biosphere, following Robin Wall Kimemerer words: “The patterns of reciprocity by which mosses bind together a forest community offer us a vision of what could be… I hold tight to the vision that someday soon we will find the courage of self-restraint, the humility to live like mosses.”

Nirit Binyamini Ben-Meir / MA IED / Royal College of Art, 2019-2021

Nirit is an Israeli born designer-artist based in London. Her work explores the interconnection between society, economy and ecology. Using participatory installations, videos and workshops, she creates experiences for humans to interact with their biosphere. Her practice uses other-than-human entities as a reflective tool for society and geopolitics.

Climate Change, Biodiversity, Post Capitalism, Care, Community